Introductory Note

I recorded this story after several hours of conversation with a Balinese friend of mine. I can vouch for his integrity and have tried to present his point of view to the best of my ability. At times, however, it is possible that I may have misunderstood his message or injected my own bias into the conversation, for which I take full responsibility. Please feel free to contact me about any errors in this article, and I will be happy to make the appropriate corrections. One last thing: although this article initially included my friend’s name, after careful consideration, I decided that it might be better to err on the side of caution, when it comes to publishing names on the web. I have therefore gone ahead and removed his name and contact information, without altering the text in any other way.

Bhikkhu Moneyya

February 25, 2020

My Story

My name is *****. I am 55 years old, married, with 5 children, and currently live in *****, Bali.

As a young man, I loved sports and trained in karate, judo and volleyball. In 1984, at the age of 19, I was appointed captain of the Bali Volley Ball Association. Later that year, our team was invited to compete in a tournament in Denpasar (the capital of Bali) with the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Police Force teams. During our game with the Army team, I managed to catch a glimpse of several soldiers who were rooting for the Army team. Their voices were loud and I could tell they weren’t happy when our team won the tournament.

After the tournament, on my way home to *****, I decided to take a swim in the ocean. I was riding my motorcycle to the beach, when several other cyclists drew even with me and forced me off the road. It turned out to be three of the soldiers who had been rooting for the Army team. One of them knocked me off my bike, and then the three of them together began to beat me as I was lying on the ground. It was easy to see that the soldiers were not Balinese, but rather from Java, which made sense, since Bali and Java were not on the best of terms at that time. They had come after me, since I had been the high scorer of the tournament.

I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t defended myself, because under President Suharto, the military had ultimate authority, and could pretty much get away with murder. Anyway, I managed to get up and grab a stick, and with my knowledge of stick fighting, was able to fend them off. Nevertheless, I had been badly beaten, and when I returned home, my father noticed my black eye, and asked me what had happened. I described to him how the soldiers had waylaid me and beaten me for nothing more than winning a game. He could see how angry I was, and I expected him to be sympathetic. Suddenly, he began to yell at me and hit me, and since my father was usually a pretty calm person, I became totally confused. “Why are you hitting me? I have done nothing wrong.”

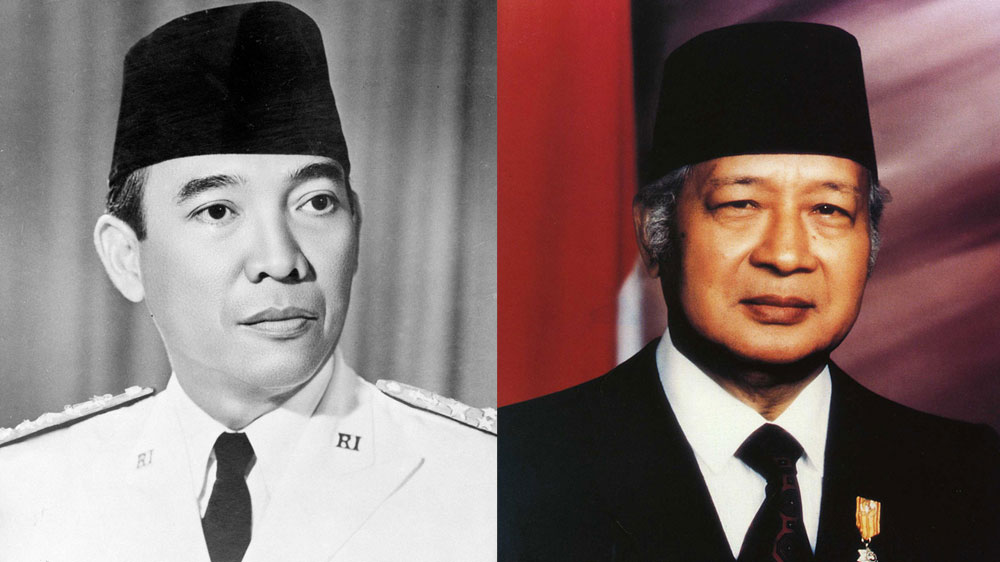

It was only then that my father told me the story of what had happened to him in 1965, when I was six months old. This is what he told me: on September 30, 1965, seven of the top generals under President Sukarno’s command were murdered in Jakarta. The murder was blamed on the Communist party, of which Sukarno was said to be a member. Suddenly, General Suharto (who was lower down in the chain of command than several of the murdered generals) found himself in a position of power, with considerable influence over the PNI (the Nationalist Party of Indonesia), which at the time, was one of possibly ten or more political parties that were competing for a voice in the parliament. In October of 1965, the PNI began a purge of the Communist Party, and the killings began.

As the conflict escalated, the fear of Communism swept over the island of Bali like a plague. Everyone was suspect, and ultimately at the mercy of the PNI. One day, an officer in the army, who was a friend of my father, stopped at our house. He explained to my father that someone in the village had accused him of being a Communist. He said, “If you stay at home, they will come to your house and kill you,” and invited my father to stay with him until it was safe to return home.

That evening, around 7:00 pm, my father left with his friend to stay in his house. Between 11:00 and 12:00 pm, a band of vigilantes arrived at our village. They waited outside our house, but since my father wasn’t there, they moved on the banjar (our community hall), where the other male villagers had been ordered to stay. According to a friend of mine who saw the killings, three of our fellow villagers were led out into the street and run through with swords. After that, the vigilantes returned to the banjar and led two more villagers out into the street. One of the villagers was run through with a sword and the other was beheaded. After that, the vigilantes burned down our banjar.

Just a note: It was said that the vigilantes had been given the names of these five villagers by the PNI. For the record, I wish to state that the only thing these men were guilty of was being leaders in our community. In the case of my father, throughout his life, he had very little interest in politics and was definitely not a Communist. By profession, he was a dancer, musician and painter, and since he was fairly well-known and respected for his skill in the arts, perhaps someone had become jealous of him. That’s all it took back in those days to be identified as a Communist.

During the three-month time period of my father’s confinement, many other innocent villagers were denounced as Communists and killed. The worst slaughter took place in the village of Tegal Badeng in Jembrana Region, where every single adult male was murdered. Of course, the vigilantes also wanted to kill my father and even knew where he was staying, but were afraid to enter his friend’s house, because he was a military man. My father was certainly lucky to have such a good friend.

The purge ended in January of 1966, and after that, my father was able to return home. Although the purge had ended, the power struggle between Suharto and Sukarno continued on until Sukarno’s impeachment in 1967, when he was put under house arrest, and Suharto became president. I think it was the lingering trauma of these events that caused my father to become so upset, when he saw that I wanted payback for what the soldiers had done to me. He told me, “If you go back and fight them again, they will kill you.”

This was one time, however, that I didn’t listen to my father. Due to my prowess as an athlete, and being a bit headstrong, I was determined to take my revenge. Every day, I rode my bike past the army barracks, until I spotted one of the soldiers. I knew he often hung out with his two friends and was willing to bide my time until I could catch the three of them together. One day I spotted all three of them, as they left the barracks. I followed them down the street on their motorcycles. When I caught up to them, I knocked one of them off his bike, beat him and left him lying on the ground. The other two got off their bikes and came for me, but I was ready for them this time and beat them both. I felt vindicated and left the scene with all the three soldiers lying on the ground.

When I got home, I was careful not to let my father know about the second confrontation, as I knew how much it would upset him. I guess I’m lucky that the three soldiers never came looking for me again. Nevertheless, the stigma of what happened to my father remained with me for years, so that when I applied to join the police force in 1985, my application was turned down on the grounds that my father was a Communist. And I wasn’t the only one to suffer – many other Balinese lost their jobs or had land that had been in the family for generations stolen from them and given to Suharto’s friends and family members. Those who spoke up about their mistreatment would get a “visit” from the military, who were not averse to using their own methods of persuasion, as I myself had discovered. During this time, the government maintained total control of the media, and those who were foolish enough to express an independent view or support a different political party were strongly censored and often made to disappear.

No doubt, it was a bad time for Bali. Most Balinese loved Sukarno, because his mother was Balinese, but that was not the only reason. He was the father of our country and helped to create a truly egalitarian and morally uplifting constitution. Based on what my father told me, his loss was a great tragedy, and the reign of terror instituted by the one who replaced him compounded that tragedy many times over. It was only in 1999, a year after the May Rebellion – when thousands of students joined together in Jakarta, to force Suharto out of office – that the media began to open up and we started to hear stories about how the CIA had masterminded and supported Suharto’s overthrow of Sukarno. We also learned how, in 1967, soon after Suharto had taken office, a US company called Freeport was granted a 91% profit share in the Grasberg mine of Papua, Indonesia – the largest gold mine and second largest copper mine in the world – leaving a whopping 9% to the country where the mine was located. Coincidence? We think not. Perhaps Suharto was merely returning a favor.

Endnotes:

- To demonstrate that Indonesia actually does possess an egalitarian and morally-uplifting constitution, I have decided to present the five basic principles that all citizens of Indonesia live by, called Pancasila. These five principles form the philosophical basis for the Indonesian constitution and are found at the end of its preamble. They are said to be inseparable and interrelated with one another, but in order to understand their significance, we need to put each of them in a historical perspective.

For example, at the time that Indonesia attained independence, it was an archipelago, consisting of many islands, with numerous ethnicities, races, religions and contrasting cultures, separated into island-states that were oftentimes in conflict with one another. One thing they all had in common, though, was a belief in divinity, or in the case of Buddhism, a belief in Dharma, i.e., ultimate truth, the supreme law. All these various religious teachings were accepted under the umbrella, “belief in an Almighty God.” Such a belief, when properly understood and practiced, helps to support a moral life and reduce animosity, thereby unifying the country and providing the basis for a just government and a free society. In this way, each of the five Pancasila supports the other four. The five Pancasila are listed below:

- Belief in an Almighty God (this boils down to acceptance of all religions)

- A just and civilized humanity (the practice of morality)

- A unified Indonesia (unity in diversity and diversity in unity)

- Democracy led by the wisdom of consensus or through representatives (a government of the people, by the people, and for the people)

- Social justice for all Indonesians (equality, justice and rights for all citizens)

- For those who would like to further investigate the possibility of CIA/US Government involvement in the overthrow of President Sukarno, please refer to the following article:

http://wvi.antenna.nl/eng/ic/pki/pds.html